Step aside minimalism, Joel Wijangco’s latest footwear exhibition is a radical love letter to the Filipino psyche: layered, irreverent, nostalgic and alive.

G. If you could design shoes for anyone, who would it be?

J. Marchesa Luisa Casati, Isabella Blow and Daphne Guinness. The people I design for want to see a more romantic world.

G. What inspired you to design footwear?

J. My grandmother’s library was stocked with old Vogue and Harpers Bazaar magazines, as a child I would see these women dressed so extravagantly, it was just fascinating.

I started designing because I wanted to say something, tell stories and words didn’t seem enough. When I was 16, a friend in pageantry harassed me into designing stuff. As a gay, my heritage was to design for the pageant queens, all my gowns were like costumes and I always paid particular attention to the detail of the shoes. Then one day I designed over 700 shoes in two days. I’d always been a talkative child but the environment I grew up in was not very conducive to talking so the shoes came out like a flood of all the things I wanted to say.

Over the years it became more honed, I realised that Filipino stories haven’t been visible to Western or more privileged audiences. That’s why you’ll see a lot of very local or anecdotal designs, like fishwives at a wet market, pedestrian experiences.

G. What inspires you now?

J. It’s a more political point of view but still the same, like the wife in the Jeepney haranguing her driver-husband over rent which became the Mahadera shoe. The people on the jeep were laughing at this woman for nagging her husband, she doesn’t want to but she is forced to, if she doesn’t who will pay the bills?

I think society forces women to play villain roles if they want to be heard, women who talk too much or are too opinionated are seen as crass or lower quality here. Now when I make shoes, it can’t help but have that thread of dialogue.

G. Why are Filipino’s so obsessed with footwear?

Shoes are expensive, we are very status driven, we like our status symbols. Society is tight-knit, we create this hierarchy of who’s doing better because then it affords a certain status and maybe a feeling of being entitled to better treatment.

For me, it started with my grandmother. I was terrified of her. She had a closet full of shoes and there was something beautiful about them, my shoes were always cheap and ratty, hers smelt nice, she had a lot of Ferragamo pumps and she would travel to the fashion houses like Chanel. One day she came home too early and I had to hide under her bed. She started walking around her room, I could see her feet in a nude pair of pumps and there was something about that felt very triggering, maybe it woke something in me. It felt removed from my reality, it felt aspirational. I also noticed that she looked different when she wore the pumps, her carriage was different. And the women in the fashion magazines looked different. I grew up with the maids, they wore slippers and they didn’t have this aura. These women felt otherworldly.

G. A great shoe should make you feel…

J. Complete.

G. What’s on your playlist at the moment?

J. CocoRosie. I also like some Taylor Swift songs and classical music like Claire de Lune if I want to calm down, Moby for drawing and Gladys Knight. I have a varied musical playlist.

G. What’s the weirdest place you’ve found inspiration?

J. When I was 8 years old, my father would take me to the wet market, the women there were not like my mum or grandmother who were small and skinny, they occupied a lot of space, they were very loud and that was very frightening for me. I disliked the wet market environment, the mud between your toes, the noise, the smell… it was overwhelming.

G. How would you describe your aesthetic?

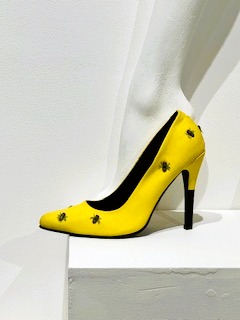

J. People have called it camp. It’s also humorous. Some of it tends to be dry, some of it is vulgar. The Nilangaw is my favorite, it’s a simple pump covered in realistic flies. If you go to lunch or a charity event and your feet are covered in flies it looks like your feet smell or you stepped in something. It happens, especially for people who can’t live in beautiful suburbs. It’s dark humour, I like humour it’s part of the human experience to find things ridiculous.

G. How does it feel to walk into your own exhibition?

J. I’ve done exhibitions in India but this is my first local one. I have a tendency to second-guess myself, also, once you start drinking your own Kool-Aid that’s when your material becomes artificial. I am scared of that. I don’t want to call myself “artist” because I don’t know if I’ve earned the right to it yet.

G. Which footwear designers do you admire?

J. From a design point I love Moschino. Louboutin cornered the market on sexy. Blahnik, Loewe, McQueen. Carolin Holzhuber, she makes me feel small. I go for magical realism and hers are like brutalism, so on the other side of how I see things, it totally boggles my mind and I just love her for that.

G. Which emotion is the hardest but most rewarding for you to translate into design?

J. Grief because people don’t wear these shoes and be like, “Oh I want go out and be sad.” Grief is something that you process. It’s one of the hardest because it’s painful. Anyone who has lost somebody doesn’t want to live through that again. I have a shoe about grief that I haven’t made yet.

G. What do you hope people will feel when they see your work?

J: Delight. If not, unsettled.

G. How do you stay true to your heritage and still appeal to an international market?

J. I’ve been criticized for not making Filipino-looking shoes because their idea of Filipino shoes is using Filipino textiles. I didn’t grow up with that but all my experiences are Filipino. The nuance escapes some people and they go for low-hanging fruit which is the visual element. I was cyber- bullied for the Sister’s Favorite which is the ramen soup, I was called race-traitor because it wasn’t Filipino food but it didn’t bother me. Ramen was my sister’s favorite, she was a teacher in Japan, if it had been Sinigang, I would have made a Sinigang shoe. She had cancer, a daily reminder of mortality over her head and I wanted to do something to cheer her up. When it came out, she cried.

G. Which designer would you most like to collaborate with?

J. Moschino, they are always poking fun at fashion. Loewe for their sense of dryness. McQueen talks to my goth heart. Louboutin if they’d have me, they are very beautiful shoes.

G. Most valuable lesson you’ve learned from a mistake or setback?

J. It pays to have experience, if you don’t, seek professional input. Some of these shoes cross disciplines – special effects to industrial engineering – it pays to have an expert.

It’s difficult to put a cost on my shoes because there’s different kinds of workforces involved. I understand why the arts is mostly populated by the rich, going through R&D, it’s expensive especially if you make mistakes. It makes me feel more learned after going through it.

G. Which part of the Filipino culture has been misunderstood or underappreciated by the fashion world?

J. We’re very amiable and the fashion world is all about being opinionated. We’re afraid to rock to boat, we want peace but sometimes this comes at the cost of our own freedom or identity. It’s how we’re wired which is a reason why I might be unpopular because these shoes are very opinionated.

G. What do you love about Manila?

J. Despite the poverty, it’s alive, it’s colourful, it could be sad but it’s not. It has a personality, nothing gets Manila down, we always find a way to find joy.

G. If you had 24-hours in Manila, what would you do?

J. I like the fringes of Manila, like Malabon where I grew up. The old Spanish houses, they are mostly abandoned now, inside there is so much beauty left behind and so much beauty eaten up by the salt of the river, age and neglect. It’s very romantic, gothic. Also, the food is amazing.

G. When you design, do you begin with a feeling, a memory or form?

J. I have to feel something.

G. How do you translate something abstract like a feeling into a physical form?

J. My nanny was flirty, she wore skimpy outfits, she wore rouge on her face, sometimes she’d have dalliances with the driver. She was treated with scorn by my grandmother. I loved her, she was nice to me and this translated to the Kulambo shoe (mosquito netting) as she used to lull me to sleep inside the netting in her room.

G. You’ve gotten a lot of attention from the exhibition. What’s next for you?

J. I want to do a homewares collection. And wedding gowns. And I want to create an installation that puts you in my shoes so you know how it feels to be a child of abuse and neglect and part of a marginalised group.

I think people are ok with the marginalisation and violence against LGBTQ people, we all live in separate realities and we are unable to engage with each other. Which is funny because social media is supposed to connect you but it serves to create walls in communities and we’re unable to extend empathy to others. It’s painful to think about it. I don’t understand the whole cruelty thing. Our hearts are big enough.

G. What sustains you?

J. Hope. It makes me feel like I can survive another day. When people lose hope, they resort to violence. It’s overwhelming if you are a person in a developing country who is not privileged, you already have to deal with so much shit, then on top of that you see these other world problems. Hope sustains me.

G. Tell me about the BOHO shoe.

The bone shoe. This was my eating disorder. You don’t know someone is going through any disorder unless you get close enough to understand what they are going through.

The gold teeth represent stomach acid staining the teeth yellow but because this is fashion, it’s gold. Nothing goes hand in hand with eating disorders like fashion. It’s a heavy shoe but you get used to the discomfort of the weight after a while, you normalise it. Like the disorder.

G. What’s the worst part of bringing your ideas to life?

When people ask me about the price of my shoes, it’s like a live-wire in my chest. I can’t discuss price, it makes me defensive, it destroys me. It’s hard to link commerce with art. Commerce wants to understand how you came to this price, art is like, “I don’t know, I just felt like it.”

I can design for other people, but for myself, it’s harder. It’s more personal and when they are sold, it feels like allowing my child to be fostered, you are giving a piece of your soul away.

I don’t know how to sell, I just want to make my shoes.

G. What’s something that no one’s ever asked you but should?

J. Am I ok?

G. Are you ok?

J. I’m hopeful.

art2wear on at Yuchengco Museum, Makati until October 2025